If You're Looking for Inspiring Technology, Grab a Guitar

It wasn’t long ago that computers were considered “high technology.” The “high” modifier mostly goes unspoken these days. When people say “tech,” they usually mean computing technology: networks, hardware, software, and the companies that build them. Other technological domains need to be distinguished with special monikers: biotech, cleantech, medtech, fintech, and the like. And increasingly, when people talk about tech, they don’t have much positive to say. This growing disenchantment stems from two sources: the business practices of tech companies and tech products themselves.

Google’s recent decision to force Gemini AI tools into all Workspace accounts exemplifies the way tech companies prioritize their business interests over user needs. The saying, “If you’re not the customer, you’re the product” may not be completely true, but it captures how it feels when companies alienate (if not outright exploit) their users. Thanks to this contentious relationship, the term “enshittification” has entered the lexicon to describe the gradual degradation of tech products once they have an established user base.

But bad business practices don’t tell the whole story. Many modern tech products disappoint by design. With a focus on capturing the attention of distracted users, designers pursue simplicity above all else, creating experiences where all meaningful choice has been stripped away. As users, we find ourselves senselessly plodding through predetermined flows or endlessly scrolling across a sea of worthless content. We’re missing out on more than just enjoyment; we’re losing our ability to imagine something better.

We’re Asking Too Little of Our Tools

A particularly apt expression of our diminished technological aspirations can be found in a viral tweet by author Joanna Maciejewska, who wrote:

This tweet resonated with so many people because the sentiment at its core is correct. Technology—not just AI—should free us from drudgery. But if that’s all we aspire to achieve, we’re aiming too low. Truly powerful technologies don’t just mitigate the tedium of daily life. Great technologies help us live in ways we never thought possible.

Of Guitars and Chainsaws

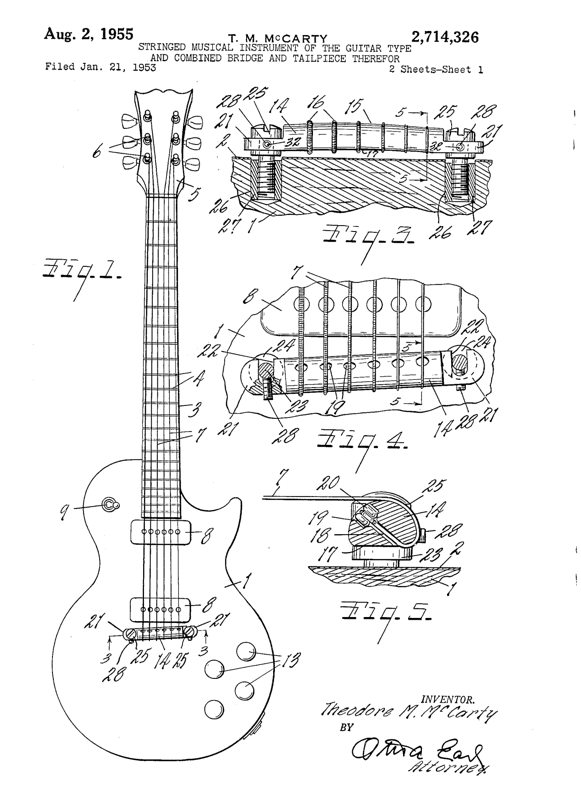

Some of the best examples of transformative technology aren’t “high tech” at all. Consider the guitar. It might not be the first thing that comes to mind as a form of technology, but that’s exactly what it is: a human-designed tool created to achieve human ends.

What makes a guitar special is that it does more than merely enhance its user’s capabilities—it creates new ones. Put another way, a guitar doesn’t just improve the human body’s natural music-making ability; it creates distinct new modes of musical expression. Generations of musicians have explored those modes without exhausting them. And, importantly, a guitar player and a piano player are not exploring a shared space of musical possibilities with different tools. Instead, each one is engaging with a distinct set of complex interactions between player and instrument. The music is shaped by the instrument, and that relationship expands the musician’s creative potential.

Another example may help illustrate this point. When you use a chainsaw to cut branches, it’s simply a better tool for an existing task. But in the hands of a chainsaw sculptor, it’s far more than a faster chisel. It’s a distinctly different way to sculpt, as reflected in both the creative process and the final work.

Modern Tools, Traditional Principles

Nothing prevents software and other “high tech” products from offering this kind of expressive range, and some do. A graphics editor like Adobe Photoshop isn’t an improved paintbrush; it’s an entirely distinct tool for visual creation. A spreadsheet like Microsoft Excel, far from being merely a better calculator, gives users entirely new ways to model, analyze, and express data. The integrated development environments (IDEs) used by software engineers don’t just make coding faster, they fundamentally change the relationship between code and coder.

The world of digital music, which dates back to the earliest days of computing, offers still more examples. Today’s digital audio workstations let musicians mix and edit tracks in ways that were impossible with the studio tools of yesterday. Audio programming languages allow artists to express music in mathematical terms. Synthesizers create entirely new instruments, free from the limitations of the physical world. It would be a mistake to consider these simply better versions of traditional music tools. They are better thought of as wholly new tools that open new creative possibilities for artists to explore.

Building Tools Worth Mastering

To create more transformative technologies, those of us in the industry must fundamentally reconsider our approach. The push to build simplistic, restrictive products for minimally engaged users is self-defeating. The tech industry serves neither itself nor its users by building every product as if it were a social media app or a shopping website.

This misguided approach was recently highlighted when an AI company’s CEO claimed that people don’t enjoy making music. Satisfying as it would be, I’m not going to spend a lot of time dropping the elbow on these shallow, foolish statements. I bring them up because they so clearly articulate how poorly many industry leaders understand their users’ needs.

Conventional wisdom in our industry would consider guitars “bad” products. They take time to learn, allow for mistakes, and can be frustrating to master. But these are not flaws; they are common characteristics of profoundly empowering tools. To be clear, I am not arguing against user-friendly design. Rather, I’m saying that too often, we build products with a feeble grasp of who the user is and what genuinely serves their interests. After all, I’ve never met a guitarist who complained that their instrument isn’t user friendly enough.

The tech industry, driven by social and commercial forces, puts ever-increasing investment behind products that are easy to pick up but have limited value. That’s the right approach in some cases, but it shouldn’t narrow our broader understanding of what technology can be. We risk forgetting that the most powerful technologies are those that grow with us and challenge us to do and be more.

The people of the future deserve tools that expand human potential. The goal shouldn’t just be to make life easier—it should be to make new ways of living possible.