Notes on Attention

I was originally working on a longer post to finish off the month of June, but I couldn’t get it to a place where I was happy with it. There was, however, an element of that post that I thought was both important and worthwhile. So, instead of what I had originally planned, I’m polishing up and posting my notes on the topic of contemporary attention economics.

The concept of the “attention economy” was originally developed by the researcher Herbert A. Simon in the early 1970s, and in recent years it has attracted renewed interest including, among others, popular books by Jenny Odell and Chris Hayes. Simon studied how information affected organizational decision making, work which earned him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1978. He observed that information had historically been a scarce resource, but that changes in computing and communication technologies were making information more abundant and accessible.

Simon’s critical insight was that information on its own is not all that valuable. To be useful, information must be combined with human attention. Intuitively, this makes sense. If you sit in a room and read a single book, the same amount of information has been transmitted whether you read the only book in the room or you were in a library surrounded by endless shelves of books. It’s your attention to the information that matters.

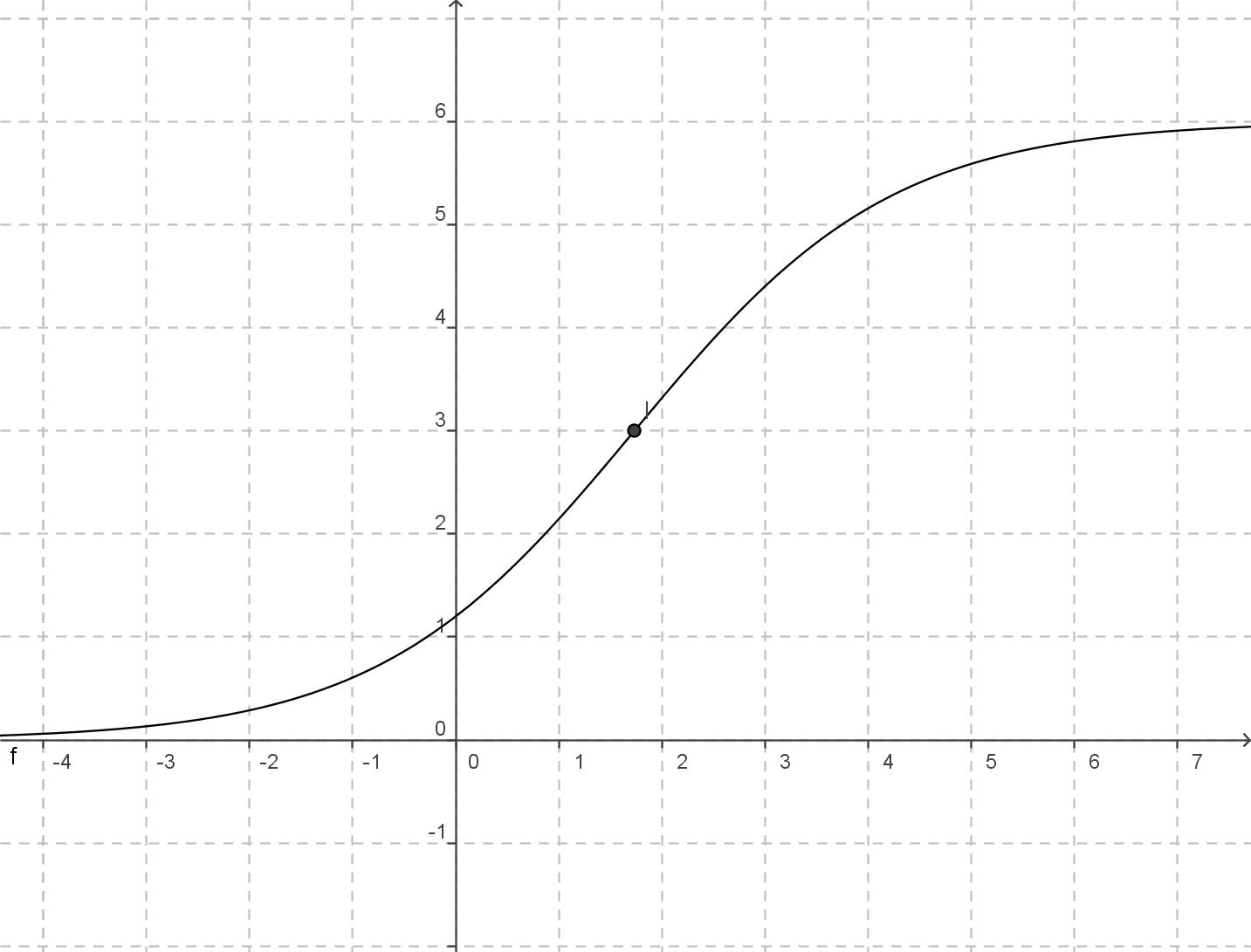

This key insight leads to an important secondary observation: attention is itself a scarce resource. In fact, attention isn’t merely scarce but fundamentally limited by the hard fact that we each have only 24 hours in a day. Simon theorized that as the supply of information grew, the scarcity of its necessary complement, attention, would become the limiting factor preventing organizations from successfully incorporating the available information.

What Simon predicted would be a concern for strategic decision makers within firms has become an issue faced by every individual on earth with a smartphone, but our challenge is complicated by conditions he never anticipated.

For one thing, the growth of companies whose business models depend on monetizing popular attention has created an incentive structure that would have been alien to Simon. These companies have innovated upon information itself, broadening and flattening it to invent the more flexible concept of “content,” a superset of information that encroaches on all aspects of human attention. Information bears some relationship to facts and data, but content can consist of anything that consumes attention regardless of its truth, meaning, or substance.

Not only do these actors have strong incentives to generate endlessly growing mountains of content, but they also face an economic imperative to capture more and more of their audience’s attention as directly as possible. This means that the amount of content is growing faster than ever, and that platforms actively drive audiences to spend more and more time consuming their content, without regard for its value to them.

The other condition Simon didn’t anticipate is the combination of global-scale social media platforms and ubiquitously-connected smartphones with push notifications, which are the technological changes that truly enabled the modern information environment. It’s characterized not only by an extreme abundance of content, but also by continuous, relentless efforts to seize the audience’s attention through distraction, interruption, heightened emotional intensity, and exaggeration of urgency, importance, and relevance. Innovations like infinite scrolling feeds, algorithmic recommendation, and engagement-based content ranking are all designed to manipulate individuals to consume more content than they would have otherwise.

Simon rightly predicted that informational abundance would cause an organization’s (or the public’s) ability to absorb new information to grow until it started to be limited by scarcity of attention. But nobody knew exactly how that limitation would manifest itself.

I suspect that what’s currently happening is the process of arriving at a new attention equilibrium as limits on content consumption become driven entirely by attention scarcity. Anecdotally at least, it feels like both online and offline, I encounter people who seem exhausted and troubled by the information overload they experience every day. If I’m right, and the world is starting to bump up against the upper limit of the public’s capacity to absorb content, it’s reasonable to be concerned about how that equilibration will happen.

Because the socioeconomic configuration that created these conditions is exploitative and unregulated, the process of arriving at this new equilibrium is most likely going to be chaotic, ugly, and painful. It would be naive to expect anything else, with platforms using any technique at their disposal to drive ever higher levels of content consumption, combining content of all types (e.g., current events, political opinion, entertainment, intentional misrepresentation, personal communications) into a single, undifferentiated stream, and competing viciously amongst themselves for an increased share of the audience’s limited time.

These changing conditions shape mass public opinion, which seems to be souring on technology in general, and they affect individual experiences as well. Consider a recent report from the American Psychiatric Association suggesting that diagnoses for adult ADHD have increased in recent years. Could this be an indication that people are feeling the effects of the fierce competitive struggle going on over their limited attentive capacity? Maybe people feel overwhelmed and conclude that the problem must be a deficit in their ability to pay attention, when what’s really happening is that their perfectly normal attention is being undermined by an information environment designed to manipulate and exploit it.

Speaking for myself, I’m looking for ways to reclaim my attention and be more intentional about how I spend it. This summer, I’m taking a more active role in choosing where I get my information from and resisting being led by algorithmic feeds. I’m also getting offline more, seeing people in person, and being more present in my community. These are small steps, to be sure, but critical ones. If you are also paying attention to your attention, I’d like to hear from you. Please let me know what steps you’re taking, what’s working, and what’s not.